Food Wastes at Harrison High School

Climate change is rapidly devouring our everyday lives, slowly forcing us to acknowledge the crisis. Often, people look to the government to take action. However, individuals can make little changes in their daily routines that can have big impacts—including schools.

Every day, Harrison High School offers a myriad of different lunch options. There’s hot lunch, which can be anything from pasta to waffles; make your own salad bar, where there are numerous toppings and dressings; make your own wrap, with different fillings, anything from breaded chicken to a tuna salad. And you can always build your own sandwich. But what happens to the warm food that isn’t eaten every day? Is it simply thrown away?

Food waste ends up in landfills, where it creates methane gas, which is far more harmful to the environment than carbon, yet the waste could be creating much more needed healthy soil by composting, instead of contributing to global warming. It’s salient that our school diminishes the amount of food waste.

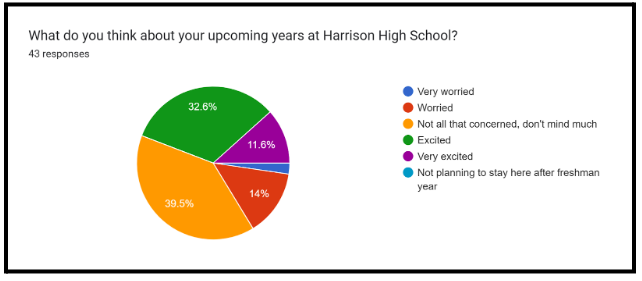

As a school, a question we need to ask ourselves is are we eating the food provided, or wasting too much of it? According to the South Dakota State University Extension, about a half of a pound of food per person is wasted every day in a public school. But is this true for Harrison High School?

Harrison High School contracts its food services to a company called Aramark. Timothy Whipple, the assistant superintendent for business, is in charge of the budget area and how it is spent at the cafeteria program, through partners with Aramark. HHS pays a fee to provide meals for students. Christine Clements is the food service manager.

Aramark has a clear system to minimize food waste. The food produced is recorded on paper so that, when there are left over, the next time they can go back to that record. For example, if they made 200 hamburgers and had 20 leftovers, the next time they would know to make a 180 and “adjust accordingly.” In special circumstances like when it’s close to a break, they often make a little less.

“If we know all the students are in, we adjust production according to how many students there are, what the weather is like, and whether the campus is closed or open,” explained Ms. Clements.

If there are cold leftovers, like carrot sticks or salad, they will use them the next day. Even hot lunches, like pasta, can then be used the next day to make a pasta salad. If it’s not reusable, however, they have to get rid of it. At the end of the day, whatever is thrown away also means wasting money, so this system and production record is taken very seriously by everyone, including the cooks and cashiers.

The production system is effective also due to how long it’s been in place. DoorDash and UberEats don’t interfere with the system, as the staff is used to them and takes them into account when planning the order.

“The waste is very minimal, usually two to four portions,” stated Ms. Clements.

But even a little bit of wasted food can have drastic consequences on our environment. Westchester County covers the cost to haul food scraps to composting facilities. Janice Kaplan, the co-chair of the Harrison Sustainability Committee, explained how the Harrison town will be starting this program this week.

“But unfortunately the schools are not included in this program,” said Kaplan. “Yes, it is possible to compost at the schools, but you’d need a few very dedicated students, teachers, and administrators on board.”

This is because the issue with composting at schools is keeping animal products out of the waste, in order to not harm them. It would cost money, time, and dedication, but it is doable.

“The more people who are educated in this the better. Everyone can compost at their own house, too. It’s pretty simple and has a powerful, positive impact on the environment,” concluded Kaplan.

The issue is also not only throwing out food when there is a surplus: there’s also the issue of students throwing out their lunches.

“Most people don’t finish their plate,” said Sami Ramirez, a freshman. “Maybe if we had different serving portions, students would waste less.”

When asked why they think that students waste food so often, Gia Ciullela, freshman, concluded, “A majority of students at Harrison High School aren’t educated enough on the effects of food waste.”

Portions are also a topic of discussion when discussing food waste control. Typically, students take too much food, or a normal portion of food might be too much, leading to the throwing away of food.

According to The World Wildlife Fund, about 530,000 tons of food are thrown away each year by schools in America. Additionally, The Chant states, 1.9% of food waste in the U.S comes from public schools.

Harrison High School values the IB profile which tells us to be risk-takers, caring, responsible, as well as principled. We must take further steps to better our environment.

“Composting is a great way to solve the food waste issues,” Mariana Orozco, a freshman at Harrison High School commented. “It allows the plants to grow underneath natural, non-chemical fertilizers. Additionally, it doesn’t send food waste to landfills.”

Although it may seem tedious, composting is a beneficial way to use wasted foods. Composting decreases the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, helps plant growth, and decreases the amount of landfill that produces greenhouse gasses.

As Aramark and the staff involved with the Harrison High school food does their part in trying to limit food waste, so should we.

How can we as a community limit the amount of food that is thrown away?

![The Fairies: [from left to right] KC Onwuasoanya, Talia Russo, Neeve Kenny, Charlotte Reville, Alexis Manalis, Abrey LaPeter, Francis Arthur, and Rosella Paniccia](https://thehuskyherald.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Play-1.jpg)